IMAGINE: What If the Tea Party Were Black?

By Tim Wise,

AlterNet

Let’s play a game, shall we? The name of the game is called “Imagine.”

The way it’s played is simple: we’ll envision recent happenings in the

news, but then change them up a bit. Instead of envisioning white people as

the main actors in the scenes we’ll conjure - the ones who are driving the

action - we’ll envision black folks or other people of color instead. The

object of the game is to imagine the public reaction to the events or

incidents, if the main actors were of color, rather than white. Whoever gains

the most insight into the workings of race in America, at the end of the game,

wins. Imagine that hundreds of black protesters were to descend upon Washington DC

and Northern Virginia, just a few miles from the Capitol and White House,

armed with AK-47s, assorted handguns, and ammunition. And imagine that some of

these protesters ‐the black protesters ‐ spoke of the need for political revolution, and

possibly even armed conflict in the event that laws they didn’t like were

enforced by the government? Would these protesters ‐ these black protesters with guns

‐ be seen as brave defenders of the

Second Amendment, or would they be viewed by most whites as a danger to the

republic? What if they were Arab-Americans? Because, after all, that’s what

happened recently when white gun enthusiasts descended upon the nation’s

capital, arms in hand, and verbally announced their readiness to make war on

the country’s political leaders if the need arose.

Imagine that white members of Congress, while walking to work, were surrounded

by thousands of angry black people, one of whom proceeded to spit on one of

those congressmen for not voting the way the black demonstrators desired.

Would the protesters be seen as merely patriotic Americans voicing their

opinions, or as an angry, potentially violent, and even insurrectionary mob?

After all, this is what white Tea Party protesters did recently in Washington.

Imagine that a rap artist were to say, in reference to a white president:

“He’s a piece of shit and I told him to suck on my machine gun.” Because

that’s what rocker Ted Nugent said recently about President Obama.

Imagine that a prominent mainstream black political commentator had long

employed an overt bigot as Executive Director of his organization, and that

this bigot regularly participated in black separatist conferences, and once

assaulted a white person while calling them by a racial slur. When that

prominent black commentator and his sister ‐ who also works for the organization

‐ defended the bigot as a good guy who was

misunderstood and “going through a tough time in his life” would anyone

accept their excuse- making? Would that commentator still have a place on a

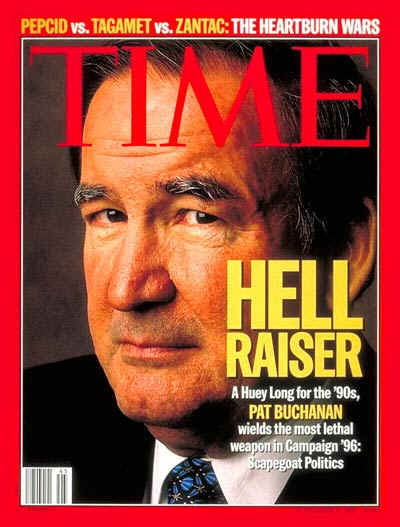

mainstream network? Because that’s what happened in the real world, when Pat

Buchanan employed as Executive Director of his group, America’s Cause, a

blatant racist who did all these things, or at least their white equivalents:

attending white separatist conferences and attacking a black woman while

calling her the n-word.

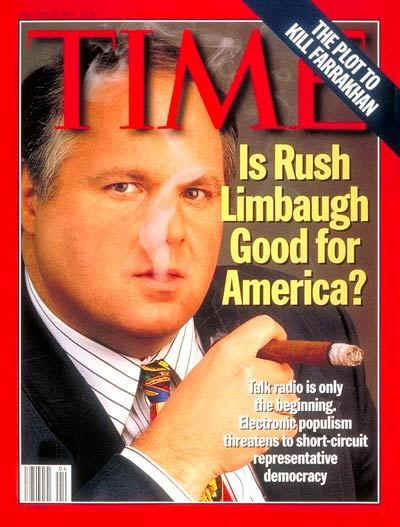

Imagine that a black radio host were to suggest that the only way to get

promoted in the administration of a white president is by “hating black

people,” or that a prominent white person had only endorsed a white

presidential candidate as an act of racial bonding, or blamed a white

president for a fight on a school bus in which a black kid was jumped by two

white kids, or said that he wouldn’t want to kill all conservatives, but

rather, would like to leave just enough “living fossils” as he called them

“so we will never forget what these people stood

for.” After all, these are things that Rush Limbaugh has said, about Barack

Obama’s administration, Colin Powell’s endorsement of Barack Obama, a

fight on a school bus in Belleville, Illinois in which two black kids beat up

a white kid, and about liberals, generally.

Imagine that a black pastor, formerly a member of the U.S. military, were to

declare, as part of his opposition to a white president’s policies, that he

was ready to “suit up, get my gun, go to Washington, and do what they

trained me to do.” This is, after all, what Pastor Stan Craig said recently

at a Tea Party rally in Greenville, South Carolina.

Imagine a black radio talk show host gleefully predicting a revolution by

people of color if the government continues to be dominated by the rich white

men who have been “destroying” the country, or if said radio personality

were to call Christians or Jews non-humans, or say that when it came to

conservatives, the best solution would be to “hang ‘em high.” And what

would happen to any congressional representative who praised that commentator

for “speaking common sense” and likened his hate talk to “American

values?” After all, those are among the things said by radio host and

best-selling author Michael Savage, predicting white revolution in the face of

multiculturalism, or said by Savage about Muslims and liberals, respectively.

And it was Congressman Culbertson, from Texas, who praised Savage in that way,

despite his hateful rhetoric.

Imagine a black political commentator suggesting that the only thing the guy

who flew his plane into the Austin, Texas IRS building did wrong was not

blowing up Fox News instead. This is, after all, what Anne Coulter said about

Tim McVeigh, when she noted that his only mistake was not blowing up the New

York Times.

Imagine that a popular black liberal website posted comments about the

daughter of a white president, calling her “typical redneck trash,” or a

“whore” whose mother entertains her by “making monkey sounds.” After

all that’s comparable to what conservatives posted about Malia Obama on

www.freerepublic.com

last year, when they referred to her as “ghetto trash.”

Imagine that black protesters at a large political rally were walking around

with signs calling for the lynching of their congressional enemies. Because

that’s what white conservatives did last year, in reference to Democratic

party leaders in Congress.

In other words, imagine that even one-third of the anger and vitriol currently

being hurled at President Obama, by folks who are almost exclusively white,

were being aimed, instead, at a white president, by people of color. How many

whites viewing the anger, the hatred, the contempt for that white president

would then wax eloquent about free speech, and the glories of democracy? And

how many would be calling for further crackdowns on thuggish behavior, and

investigations into the radical agendas of those same people of color?

To ask any of these questions is to answer them. Protest is only seen as

fundamentally American when [white people] those who have long had the luxury of seeing

themselves as prototypically American engage in it. When the dangerous and

dark “other” does so, however, it isn’t viewed as normal or natural, let

alone patriotic. Which is why Rush Limbaugh could say, this past week, that

the Tea Parties are the first time since the Civil War that ordinary, common

Americans stood up for their rights: a statement that erases the normalcy and

“American-ness” of blacks in the civil rights struggle, not to mention

women in the fight for suffrage and equality, working people in the fight for

better working conditions, and LGBT folks as they struggle to be treated as

full and equal human beings.

And this, my friends, is what white privilege is all about. The ability to

threaten others, to engage in violent and incendiary rhetoric without

consequence, to be viewed as patriotic and normal no matter what you do, and

never to be feared and despised as people of color would be, if they tried to

get away with half the shit we do, on a daily basis.

Game Over.

April 25, 2010

So let’s begin.

http://www.alternet.org/story/146616/what_if_the_tea_party_were_black?page=e

Ted Nugent

Pat Buchanan

Pastor Stan Craig

Tim McVeigh

Rush Limbaugh

On or about April

23, I shared the NY Times article by Skip Gates

On or about April

23, I shared the NY Times article by Skip Gates

At the time, I promised (or threatened) a reply. It is almost impossible not to reply to such a statement except in a lengthy way, unfortunately, but I would respectfully offer the following points for consideration. -- DGT

Dr. Henry Louis

“Skip” Gates, Jr. has what it is probably fair to say

that most academicians lack, which is the quality -- for

better or worse -- of being a showman. He

is credited, along with Dr. Cornel West, with having

restored to American society the role and persona of the

“public intellectual,” and they have done so with the

added coup of making that role one that is dominated by

African American scholars. As a showman,

Dr. Gates has demonstrated an aptly remarkable knack for

attracting the spotlight of attention, as in the brouhaha of

his confrontation with the Cambridge, MA, police as he

“broke into his own home,” which even garnered the

attention and involvement of the President of the United

States. This follows less publicized

controversies, such as the television series of his trip to

Africa, which left many of his African/American countrymen

and women frankly embarrassed to have been represented that

way to dignitaries and common folks of the Motherland.

As

a scholar, it is probably fair to say that he has been trading

in the market value, to some, monetary or otherwise, of

keeping the issue of “race” alive and important. This is not to say that it is unimportant – as too

many people every day pay the price of racist oppression,

discrimination and exploitation. But it is

to recognize the scientific reality that our commonly held

notions of “race” are a myth, as modern DNA evidence has

proven again and again. (The Human Genome

Project revealed that fully 98.2% of all human DNA is

identical, so that only 1.2% of our entire genetic makeup

accounts for ALL of the differences we perceive among

individuals, including height, body type, and certain

personality traits, as well as what are called

“phenotypical” [“racial”] characteristics. Indeed, one DNA study showed that the two ethnic groups

that were the most genetically similar were Australian

Aborigines and Finnish Laplanders. So much

for the “scientific” basis for genetic entitlement to

unearned privileges.)

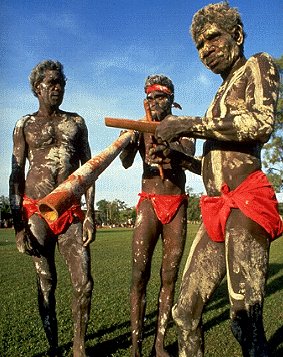

Australian Aborigines

Not

only is “race” an arbitrary and mythical construct which

originated in the era of European exploration and

colonization, with its doctrine of “White Supremacy,” as a

tool of racism itself. To keep the concept

and the issue alive, by focusing on “race relations” is,

in fact, a backhanded way of assuring the White Supremacists

that they are still important, that they still have the power

to control other people’s lives. (Racism

has a very hard time accepting the fact that, even during the

slavery era, enslaved people had many more important things to

think about and to do than the fact that they were legally

enslaved.)

That,

from the lens through which I am looking, is the backdrop for

this latest Gates flourish, entitled “Ending the Slavery

Blame-Game,” which appeared in The New York Times of April

22, 2010. The basic premise of the article

is that the history of slavery -- and its continuing

aftermath, which have engendered an inevitable discussion of

reparations, has been skewed by reparations

activists to focus on the misdeeds of “white” people,

while ignoring the role played by Africans in supplying the

slave ships with captives in the first place.

As a showman, Dr. Gates has found yet another topic to throw on

the table that is guaranteed to be sensational, and no doubt

will stimulate the kind of discussions and debates that will

keep his name on the lips of many for some time to come.

(The Cambridge Cop coup had pretty much run its course

anyway.) As a scholar and public intellectual, he has put together a well-researched essay,

worthy of both academic peer review and popular consumption,

which addresses one of those historical realities that is

bound to be “uncomfortable” for some, while perhaps being

“comforting” to others. In any case, it is hard to argue that it is not a topic whose time has come

for an open

The

questions that remain are whether this particular article

contributes to the better-being of society by offering useful

and constructive information, and, if so, what makes it

useful. The first of these questions has to

be answered by society itself; the article is literally what

we make it, but the answer to the second has much to do with

what we can make of it.

Amongst

the reactions that this essay is bound to generate, my own

cannot promise to be of the same academic quality, and

represents only one response among hundreds of millions of

possibilities, but it is also the same response that I have

offered for years. We can begin by accepting the basic truth of Gates’ premise, that a)

Africans sold Africans to the so-called “slave traders,”

and that this could not have been accomplished except with

African participation and support; and b)

the question of reparations must take this into account.

Of

course, none of this is new. This point has

been made many times in many places (Black conservative

commentator Thomas Sowell made the same point, as I recall,

back in the 1990s, for example) , but not perhaps with

the impact of an article in a prominent newspaper with a

showman-scholar’s by-line. And the

response to it is new either. While it may

be quite true that “Africans sold Africans,” this is

frankly inane because it is like saying that Europeans killed

Europeans during World Wars I and II. The

nations of Europe which fought wars and captured prisoners

whom they effectively enslaved did not consider themselves

fighting fellow Europeans who all shared the same culture or

language, but as separate nations, as in Africa.

Why

would it be logical to expect Africa, a continent several

times the size of Europe, with literally thousands of

different cultures and languages, to be any different. As has been often observed by educators striving to

undo old stereotypes, “Africa is a continent, not a

country.” Different nations of Africans

fought and took captives from other nations. Arguably,

the same can be said to be true throughout the human race in

one form or another.

Moreover,

the idea of ridding one’s country of its enemies and

unwanted population by sending them on ships across the ocean

was not unique to Africa. It was common

enough in Europe to dispose in this manner of convicts,

debtors, indentured servants, persecuted religious sects, and

others with a reason not to stay in Europe. To

this might be added the practice of “Shanghai-ing”

sailors, who would awake from an induced drunken stupor or a

knock on the head, aboard a ship far out at sea, as part of

the crew.

These

points may prove that the behavior which Dr. Gates ascribes to

Africans might be more universally human than racist

propaganda would suggest, but it does not negate his basic

point that, if it is a matter of identifying the perpetrators

of the crime of “slave trading,” then Africans must be

included (just as Europeans must be recognized as the

slaughterers of fellow Europeans). However,

he seems to ignore some of the factors that brought about this

African involvement in this nasty business. He

states that “The sad truth is that without complex business

partnerships between African elites and European traders and

commercial agents, the slave trade to the New World would have

been impossible, at least on the scale it occurred.”

While

he cites the works of distinguished and knowledgeable scholars

like John Thornton and Linda Heywood, or David Eltis’

extensive database on slave ship voyages, he seems not to have

consulted such authoritative works as Dr. Eric Williams’

classic study of “Capitalism & Slavery” or the late

Dr. Walter Rodney’s “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa.” Such works demonstrate how these “African elites”

were often artificially created by being armed and enriched by

the European traders in exchange for their collaboration. Walter Rodney insightfully discusses the effects of

such strategies as “economic blackmail”: essentially a

proposition in which the trader says to a coastal African

chief, “If you do not take our guns and procure ‘slaves’

for us, we will sell our guns farther down the coast, and

those people will use them to capture you.”

Rodney

also even discusses the effect of inflation: Once the cowrie

shell was established as a form of money, because of its

rarity, trade could be conducted at established rates of

exchange. However, as European explorers

found locations elsewhere where cowries were abundant, they

could return to these old trading places and flood the local

economy with money, thereby depressing the value of

everything, creating poverty, and then exploiting that

situation to coerce people to deliver “slaves.”

And,

of course, there is the basic fact, as pointed out by Dr.

Alexander Falconbridge, the English ships’ surgeon who wrote

the lesser-known commentary that accompanied the 1789

publication of the famous image of the Slave Ship Brooks,

that there would have been no African participation in this

“trade” in human beings if there were not slave ships

creating the demand in the first place.

These

practices, added to the depopulation itself that was caused by

the “slave trade” succeeded in disrupting social

organization and such systems as agriculture and defense,

which became a downward spiral and a vicious cycle, of which

we see the results today.

The

reality of these practices is not a denial of the fact that

there were corrupt and greed-driven individuals who were only

too happy to gain privileges by trading with the Europeans

that their own people would never have accorded them, and to

be made into a new “African elite.”

While

Dr. Gates suggests that “Advocates of reparations generally

ignore” the fact of African participation, choosing instead

to believe romantic notions of kidnapping by evil white men,

the fact, at least as I have known it, has always been that

Black people never denied African involvement. Indeed,

it has become something of a fixture in modern culture to

remember that “some of those that willingly sold us to the

ships are still with us,” as we witness the continued

propagation of these collaborator “elites.” This

allegation of intellectual laziness and dishonesty on the part

of those who espouse reparations borders on some unfortunate

stereotyping on Dr. Gates’ part.

Maybe

his suggestion is justified by the fact that the reparations

issue, the second matter that his article addresses, has been

bandied about so much by people who have not given it much

more than superficial thought, and these may be the

“advocates” to which he refers. His

argument would be much stronger if he addressed the more

reasoned aspects of the debate, put forth by serious thinkers,

but sometimes showmanship works better when it is knocking

down a straw man that the performer himself has created, with

a little help from his unknowing allies, than more honest

debate.

In

the spirit of full disclosure, while I may not be one of the

most serious thinkers, I do believe that I am far from alone

in considering this vital issue of Reparations beyond the

lightweight level that Dr. Gates evokes. For

what it is worth, my own longstanding position on the

Reparations issue may not be one that gets wide agreement, but

it is one that I hope will contribute something useful and

constructive to the discussion:

Although other groups of people have received

payments as reparations for past wrongs, reparations for the

African World cannot and should not be in money, for at least

two reasons: a) There is simply not that much money on the planet, to pay for five

centuries of slavery, colonialism, and

their continuing aftermath; and

The only way for the guilty parties to pay would be for them

to remain sufficiently wealthy to do so, which means

continuing their existing practices, and all of the resulting

existing problems, such as global sweatshops and militarism to

defend their interests.

Other groups who have received reparations

payments have gained them as a result of successful legal

action after the crimes – such as the Nazi Holocaust or the

unjust internment of Japanese Americans – have ceased.

The crimes against the African World did not cease with

the end of legalized slavery, but continued with terrorism

during Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, and continuing

discrimination and exploitation, including “resegregation,”

today. Moreover, for this very reason, it

is even questionable that a court can be found where a truly

fair hearing of the case can take place.

The whole notion of what constitutes fair

reparations needs to be revisited and redefined, and must be

on a global, not just a national scale. Cancellation

of all outstanding debt supposedly owed by African World

nations, and the removal of all land mines from countries like

Angola (and not by underpaid Africans being placed in harm’s

way) might be a beginning. The Reparations

question is much more of a matter of “restorative justice”

than, say, revenge, or arbitrary cash payouts with no real

change in the system.

In other words, as with all social demands by

the African-descendant population in the past, which have

always benefited all segments of the population, the

Reparations issue for African Americans is the last and

ultimate one to be resolved. And it

can only be done in a way that all people benefit, and that

the African World is restored to self-sufficiency and

self-determination going forward.

That

is all pretty much oversimplified, but it reflects, I think, a

better basis for discussion than the false stereotypes and

supposed “solutions” (such as cash payouts – since this

is in someone else’s control) that can be only temporary at

best.

As

to the question of whether Africans owe reparations to those

of the African Diaspora, as Dr. Gates points out, African

leaders are among the first to recognize that wrongs were

committed, but their situation is much different, it seems to

me, from that of the actual enslavers in this country and

elsewhere, and the difference is not just in their skin color.

The focus has to be on who profited the most from

slavery, and what kind of “restorative justice” the

various parties can offer in order to establish real equality.

This

is all very complex, especially while Africa is still being

destroyed by situations like those in Darfur, Uganda, and the

Congo, and recently in Rwanda, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, all

with the eager encouragement of foreign arms dealers.

Who can deny that there is African participation in all

of these horrors, but this begs the question of how and why

these conflicts began, and also of why the many heroic

efforts, also with full African participation, to remedy or

prevent these ills receive neither the support nor the press

coverage that the perpetrators regularly receive.

It

is not about blaming “others” – as the title of Gates’

article suggests – but about solving a profound human

problem that depends heavily on the destiny of African and

African-descendant nations and peoples and how much they are

being systematically prevented from having true independence

and self-determination. (A major tool for

preventing this is precisely the artificial creation of

outside-dependent “African elites.”) No

one can deny that this is a matter of African responsibility,

even though African “elite” participation in it (like

African participation in, say, heroin dealing or other

destructive practices) is a fact of life. The

idea is to find solutions rather than perpetuate the problems,

even by continuing to discuss them. With

solutions, the “blame-game” will take care of itself, with

no finger pointing needed on our part.

What

appears to be the consensus on this Reparations question, and

why the focus is on European and European-descendant

perpetrators of the crimes of slavery and “slave trading,”

while appearing to avoid indictment of the African

participants, is that the Africans who were

involved and their descendants are all very keenly aware of

the moral and spiritual currency in which the accounts for

past misdeeds will be reckoned. (It is not

for nothing that we see performances like what Gates describes

on the part of the President of the Republic of Benin.)

Justice for African participation will, arguably, take

care of itself.

However, if

Reparations continues to be an issue at all, it is precisely

because “mainstream America” generally recognizes no

responsibility for having committed an enormous crime (added

to the genocidal “removal” of the Native peoples).

To hear most Americans, including the political

leadership, all of that was OK, even God-ordained, as if

nothing wrong was ever done.

And

this is the basic point. It is ironic that Skip Gates'

article talks about "ending the blame game" when

what it really does is only to continue it. African

responsibility for its part in the "slave trade"

has never been denied by any serious thinkers in the Black

community that I know of. If anything, in the

tradition of "keepin' it real" and eschewing

phoniness, it has always been fully acknowledged. What

this article seems to be aimed at is keeping America's myths

of innocence alive, by "letting white folks off the

hook," as it were, by reassuring them that they are

absolved of the guilt, since it was, after all the Africans

who sold the Africans and none of this could have happened

if that were not the case.

It

is true enough that no living persons who might categorize

themselves as "white" today had any hand in the

crimes of "slave trading" and slavery, so there is

no guilt anyway. The challenge, however, is for the

entire nation (and world, for that matter), having inherited

the burden of that history and its continuing consequences

(including the fundamental distribution of material wealth

and political power, for example), to come to terms with

this burden and whether we intend to pass it on to future

generations (or even, by ignorance, unintentionally pass it

on.)

The

single most dominant social factor in shaping the last five

centuries of human history has been the doctrine of “White

Supremacy,” concocted in the wake of western European

exploration and colonial expansion. (“Their gain

shall be the knowledge of our Faith, and ours shall be such

wealth as their country hath,” as glorified pirate Sir

Francis Drake is quoted as stating baldly.) This

doctrine has no scientific or moral justification, and has

only been maintained and supported by violence, whether

actual or threatened, whether physical or psychic, but

always present.

In

these recent centuries (a mere nanosecond of human history),

this corrupted mindset has had global reach and a

“white” face, but it is a timeless human challenge.

There will always be would-be and wannabe oppressors and

exploiters of their fellow beings. If there is any

“blame game” to be sorted out, it is in how each one of

us individually either resists or collaborates with those

forces, or, conversely, asserts a society in which such

impulses are contained by predominance of sanity.

Dr.

Gates would serve our race – the human race -- much better

if he had applied his formidable scholarly and showmanship

skills to addressing this issue on a more serious and

purposeful basis that would contribute to the solution

rather than the problem.

Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

July 16, 2009

Wole Soyinke, Cornell West, Gates

Dinizulu Gene Tinnie

Published on The Root (http://www.theroot.com)

When It Comes to the Slave Trade, All Guilt Is Not Equal

By: Michael A. Gomez

Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr.'s op-ed in the New York Times, "Ending the Slavery Blame-Game" (April 22, 2010), is a provocative piece whose core argument is the following: Because African elites were involved in the transatlantic slave trade as commercial partners with Europeans, blame is necessarily and equally assigned to them as well, spreading guilt around so much as to render it meaningless.

Professor Gates has assumed controversial positions before. Though his recent article will rankle many (which I suspect is his intention), I want to suggest that there is much to gain from a healthy and informed debate on this matter. And there is much to debate. The fault line of "Ending the Slavery Blame-Game" lies not in its estimates and statistics, but in its interpretation.

To begin, there is no denying that, as a direct result of the growing demand for enslaved labor in the Americas, West and West Central Africa became theaters of increasing violence and warfare from the 15th to the 19th centuries. Sugarcane, indigo, cotton, tobacco and coffee production were all labor-intensive enterprises that required large numbers of workers, which for various reasons could not be supplied from either Europe or indigenous America. The African continent just happened to be located between Europe and the Americas and became identified as the leading source of that labor.

Given the foregoing, it would be difficult to dispute that European and American demand fueled the transatlantic slave trade. Europe and America provided the capital, built and commanded the ships, and created the plantations that absorbed those captured. There are multiple studies demonstrating that the rise of American and European wealth in that period bore a strong correlation to the slave trade. Stated differently, the emergence of the West was largely at the expense of African labor. The concept of reparations is therefore not simply concerned with suffering, but also with the question of who should rightly benefit.

Since it was Europe and America that were responsible for the broad design and implementation of the slave trade, to what extent can we assign blame to those African elites who facilitated that trade? This is a fair question, for as professor Gates correctly asserts, there is no doubt that Africans played a role. But what does it mean to say that African elites or even African kingdoms were involved in trafficking human beings? What was the nature of that involvement, how extensive was it and how far did it reach?

The African environment created by external slave trades (the transatlantic sector was only one of several) became increasingly unstable from the 15th to the 19th centuries. Captives from wars (fought over religion, land, the control of trade routes and in some cases for the express purpose of creating captives), who would have been killed or absorbed into the conquering society in prior times, now found themselves funneled toward the coast, where they would eventually be taken to the Americas and elsewhere. Along the way, they were joined by others who were similarly bound, but for other reasons. (They were accused of crimes or were victims of kidnapping, etc.)

As the tentacles of the trade reached deeper into the hinterland, more communities became susceptible and responded by defending themselves. Ironically, captives taken by those acting in self-defense were also often fed into domestic commercial relays that ultimately led to the sea. Relations between communities became increasingly complex, but the point here is that individuals and populations "involved" with the slave trade were drawn in for many different reasons. It is difficult to imagine assigning equal culpability to a community fending off the slave trade with the European nations bankrolling and in ultimate control of the entire affair, especially when those European nations were providing the weaponry.

Those Africans whose slaving activities were far more predatory, and who were the principal operatives of the trade, were those with guns, and those guns were supplied by Europe in a manner that grew exponentially and in keeping with the escalation of the slave trade over the centuries. The situation is entirely analogous to the current cycle of drug violence in Mexico. As was true of most Africans during the period of the slave trade, the vast majority of Mexicans have nothing to do with the rise of horrific bloodletting directly linked to the demand for cocaine and heroin in the United States.

So African involvement has to be qualified, as it varied and secondary to that of European and American powers. Further, such involvement is clearly central to related matters such as reparations. For even if African elites were as guilty, does that excuse European and American participation? And even if African states were equally culpable, from which African governments could we expect reparations?

These are critical questions, because the logic of reparations is that compensation is to be derived from corporate bodies -- states, businesses, universities, etc. -- that both participated in and benefited from slavery and the slave trade. The United States, France, England, Spain, Portugal, Brazil, etc., were all present (in one form or another) during the slave trade, and they all continue to exist. They all benefited from the trade and arguably owe a great deal to those whose labor was exploited but whose persons were abused for centuries. In contrast, European colonialism did away with African sovereignty; the Dahomey and Asante of the 18th and 19th centuries are no more.

To be sure, there are a seemingly endless number of questions and variables that would make the implementation of reparations unlikely, or at least unwieldy, but the practicality or viability of reparations is a separate issue from its moral validity. It is beyond debate that Africans and their descendants suffered egregiously. Those responsible for that suffering may no longer be with us, but, in many cases, the institutions and forms of government to which they contributed remain. On their way to power and wealth, they caused incalculable suffering to millions; their descendants continue to suffer disproportionately all over the Americas. What does this continued suffering have to do with the past, and what are the responsibilities of those who benefited to those who did not?

While taking issue with professor Gates on some of these questions, I commend him for resurrecting them and reminding us of their complexity. Perhaps his greatest service in this regard is bringing into sharp relief the complicated and arguably neglected set of relations between Africa and its disapora, as there is certainly a need for healing and reconciliation between the two. President Obama could certainly serve as a bridge, but perhaps not the one envisaged by professor Gates. Rather, he may be better positioned to ford a different divide between those long separated by time and space and by circumstances over which they exercised little control.

Michael A. Gomez is a professor of history and Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies at New York University. You can learn more about his work here.

- blame and slave trade

- henry louis gates jr.

- Politics

- reparations

- slave trade

- transatlantic slave trade

SOURCE

Links:

nytimes.com/2010/04/23/opinion/23gates.html

history.fas.nyu.edu/object/michaelgomez

www.theroot.com/sites/default/files/218734.jpg

By Barbara Ransby --

colorlines.com

The

celebrity academic's New York Times editorial is not

only a disservice to history, it comes at exactly the

wrong time in our discourse on race.

In a recent New York Times editorial, entitled,

“Ending

the Slavery Blame Game,” Harvard

Professor Henry Louis Gates calls on the United

States’ first Black president to end the nation’s

sense of responsibility for the legacy of slavery.

It is a pernicious argument, well suited to the

so-called “post-racial” moment we are in. Like the

erroneous claims of “post-racialism,” in

general, Gates’ editorial compromises rather than

advances the prospects for racial justice; and clouds

rather than clarifies the history, and persistent

realities, of racism in America.

Social

Activism is not a hobby: it's a Lifelong Commitment. -- s.e.

anderson "The Black Holocaust for Beginners"

www.blackeducator.org