March 31, 2004

COURAGEOUS WOMEN ARE ON THE MOVE

GET

UP, STAND UP! RITA MARLEY

By Stephan Talty

Rita Marley (widow of Bob) has not only kept up the fight, she's bounced out of her late husband's shadow, taken an entire African nation under her wing, and kicked off a remarkable second act. Rock star widows are supposed to fade into the California sunset, shopping on Rodeo Drive and faithfully seeing their plastic surgeons every other year. Rita Marley has gone a different route. The widow of reggae great Bob Marley has journeyed to Africa to help the people her husband sang about so piercingly. "To move forward," she says, "you have to return home."

Rita has returned to the continent that Bob considered his true birthplace. She's bought a house in Ghana and put much of the money that pours in from his record sales to good use: In addition to supporting her 38 grandchildren, she has essentially adopted 34 Ethiopian children orphaned by AIDS, famine, and war, helping to provide for their education and everyday needs. For one Ghanaian village, her foundation built a clean water supply, classrooms, a day care center, and roads. It distributes basics like food, medicine, books, and toothbrushes.

April 2004 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine

Women's History Month

Women's rights & Black liberation

'Ain't I a woman'

By Leslie Feinberg

Women - Black, Latina, Native and White were a significant activist force in the 18th and 19th centuries to abolish chattel slavery in the South of what is now the United States. And women played a strong role against slavery, internationally, as well. Many of the 60,000 Irish people who signed an anti-slavery petition, in 1841, for instance, were women.

In this country, women were often in the leadership of crowds that freed Black people in the North who had escaped enslavement and were being forcibly returned after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1793. A large group of Black women in Boston in 1836, for example, liberated two Black men from the custody of the sheriff who was returning them as "fugitives" to shackles in the South.(1)

Vigilance committees that united Black and White were organized throughout the North to stop bounty hunters and arrests, and to liberate those already in custody. Thousands- Black and White, women and men- took part in rescue attempts, many of them successful.

Black women and White women formed female anti-slavery societies. Some were all White and refused admission to Black women. Some, striving to unite against racism, had Black and White members and, in a few cases, supported the right of Black people - North and South - to self-determination. And Black women organized their own network of groups that had an anti-racist, as well as anti-slavery focus.(2)

While wealthy White women and relatively well-to-do Black women often played leading roles, poorer women activists- including Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Frances E.W. Harper and Maria Stewart - were prominent leaders in the Abolition movement, as well. And the ranks of the burgeoning movement were filled with washerwomen, domestic servants and factory workers. But all women who became active in the movement to end slavery faced sex and gender barriers that forced them to battle to expand their rights as women in political, economic and social spheres.

White women from all classes were trying to shatter the dominant, bourgeois ideals of "true" womanhood held aloft by the Northern patriarchal industrialist ruling class - the "cult of true womanhood." Free Black women in the North were struggling, together with their entire oppressed nation, to overturn enslavement in the South and to fight for economic and social rights in the North under wage slavery. As a result, many Black women fought to shatter the vicious White-supremacist stereotypes of African women in relation to the "virtues" of White womanhood.

Knocking over the 'pedestal' European colonialists had attempted to wipe out any knowledge of the more complex organization of sex and gender prevalent in Native and African nations as part of its cultural genocide. Kidnapped African peoples represented many nationalities, spoke different languages and came from diverse cultures with beliefs about sex and gender that contradicted the rigid and repressive dominant concepts in 19th-century North America.

The same was true for diverse Native nations.

-

When the Spanish invaded the Antilles and Louisiana, "they found men dressed as women who were respected by their societies. Thinking they were hermaphrodites, they slew them."(3)

-

Conquistador Nuño de Guzmán, describing his assault on indigenous people in 1530, wrote that the last Native person taken prisoner, who had "fought most courageously, was a man in the habit of a woman."(4)

-

The group Gay American Indians has documented what they refer to as alternative gender roles in 135 Native nations on this continent.(5)

The tremendous organizing and actual battles to abolish slavery gave rise to the demand to win greater sex and gender freedom. It was like a fresh wind that lifted the heads of many who strived for progressive societal change.

The following is a description from the November 21, 1866, New York Herald of those who attended the American Equal Rights Association, founded in May of that year to weld the struggles for Black and women's suffrage into one campaign. It's raw and offensive, yet it describes the breadth of the movement at that time and in language not unlike that of right-wing pundits today.

"All the isms of the age were personated there. Long-haired men, apostles of some inexplicable emotion or sensations; gaunt and hungry looking men, disciples of bran bread and White turnip dietetic philosophy; advocates of liberty and small beer, professors of free love in the platonic sense, agrarians in property and the domestic virtues; infidels, saints, Negro-worshippers, sinners and short-haired women. Long geared women in homespun, void of any trade mark, and worn to spite the tariff and imposts; women in Bloomer dress to show their ankles, and their independence; women who hate their husbands and fathers, and hateful women wanting husbands."

'Cross-dressing' charge set back the movement

The Dress Reform movement in the mid-19th century, for example, challenged the law that declared only men could wear trousers. The Bloomer movement, which advocated replacing rib-snapping tight corsets and long skirts that dragged in the manure-filled streets with flowing pantaloons was met with violent outrage from the patriarchs of property.

It was literally labeled "cross-dressing." Opponents quoted from the Bible, frequently Deuteronomy 22:5: "A woman shall not wear anything that pertains to a man, nor shall a man put on a woman's garment, for whoever does these things is an abomination to the Lord your God."

While at least one of the leaders of the Dress Reform movement, Dr. Mary Walker, actually was a female-to-male cross-dresser, everyone who advocated rights for women became targets of anti-gay, trans-phobic and anti-intersexual bigotry. Alongside White supremacy, this divide-and-conquer attack thundered from on high, from the bully pulpit of newspaper editorials to the church dais.

When suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton wore bloomers to an 1852 women's rights convention, a journalist accused her of dressing like a man. But when organizers of a predominantly White, male, anti-slavery convention tried to deny Lucy Stone the right to speak because she was wearing bloomers, the noted Abolitionist Wendell Phillips successfully defended her against the gender-baiting. Phillips replied, "Well, if Lucy Stone cannot speak at that meeting, in any decent dress that she chooses, I will not speak either."(6) However, the inability to stand up to the storm of sex- and gender-baiting resulted in the decline of the Dress Reform movement. And this defeat was a setback for the Abolition movement, as well, in which women played such an important role.

'Ain't I a woman?'

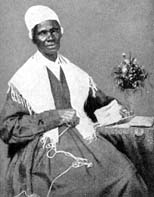

But leaders of the most oppressed demonstrated great courage and clarity in the face of gender-phobic and trans-phobic epithets and anti-gay slurs. The rumor that she was really a man disguised as a woman hounded Sojourner Truth. In Kosciusko County, Indiana, a White doctor who led the pro-slavery forces disrupted her from speaking at an anti-slavery event.

"Hold on," he shouted. "There is strong doubt in the minds of many persons here regarding the sex of the next speaker." He demanded that this African woman, who had been stripped and whipped by slave owners, bare her breast to the women present. Sojourner Truth strode to the podium. She stood some six feet tall. Her voice was described as "rolling thunder." "I will show my breast, but to the entire congregation," she told the gathering as she undid the buttons. "It is not my shame but yours that I do this."(7)

Ministers who disrupted a women's rights convention in Akron, Ohio, in 1851 also baited her about being a man. Truth, the only Black woman present, reportedly rolled up her sleeve to exhibit the "tremendous power" of her muscles. She silenced the room with her powerful challenge: "I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as any man- when I could get it- and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman?"

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass and the other 30 men who attended the first women's rights conference in Seneca Falls, N.Y., were labeled "hermaphrodites" and "Aunt Nancy Men." But Douglass, who had escaped slavery only a decade earlier, never backed down. "I'm proud to be known as a women's rights man," he wrote and said publicly, again and again.

References: (1) Herbert Aptheker, "The Negro in the Abolition Movement." (2) Shirley J. Yee, "Black Women Abolitionists: A Study in Activism, 1828-1860." (3) Cora Dubois, cited in Richard Green, "Historical and Cross-Cultural Survey: Sexual Identity Conflict in Children and Adults." (4) Francisco Guerra, "The Pre-Columbian Mind," cited in Walter Williams, "The Spirit and the Flesh: Sexual Diversity in American Indian Culture." (5) "Living the Spirit: A Gay American Indian Anthology." (6) Anne L. Macdonald, "Feminine Ingenuity: How Women Inventors Changed America." (7) Jacqueline Bernard, "Journey Toward Freedom: The Story of Sojourner Truth."

See also, Former slaves backed early movement (April 1, 2004)

Next: The most oppressed fought in solidarity with women's rights

Reprinted

from the March 25, 2004, issue of Workers World newspaper

(Copyright Workers World Service: Everyone is permitted to copy and

distribute verbatim copies of this document, but changing it is not

allowed. For more information contact Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY

10011; via email: www@wwpublish.com.

-

Subscribe wwnews-on@wwpublish.com.

-

Unsubscribe wwnews-off@wwpublish.com.

-

Support independent news http://www.workers.org/orders/donate.php

Sojourner Truth

c.1797-1883

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

(1815-1902)

Harriet

Tubman

c.1820-1913

Francis

Ellen Watkins Harper

(1825-1911)